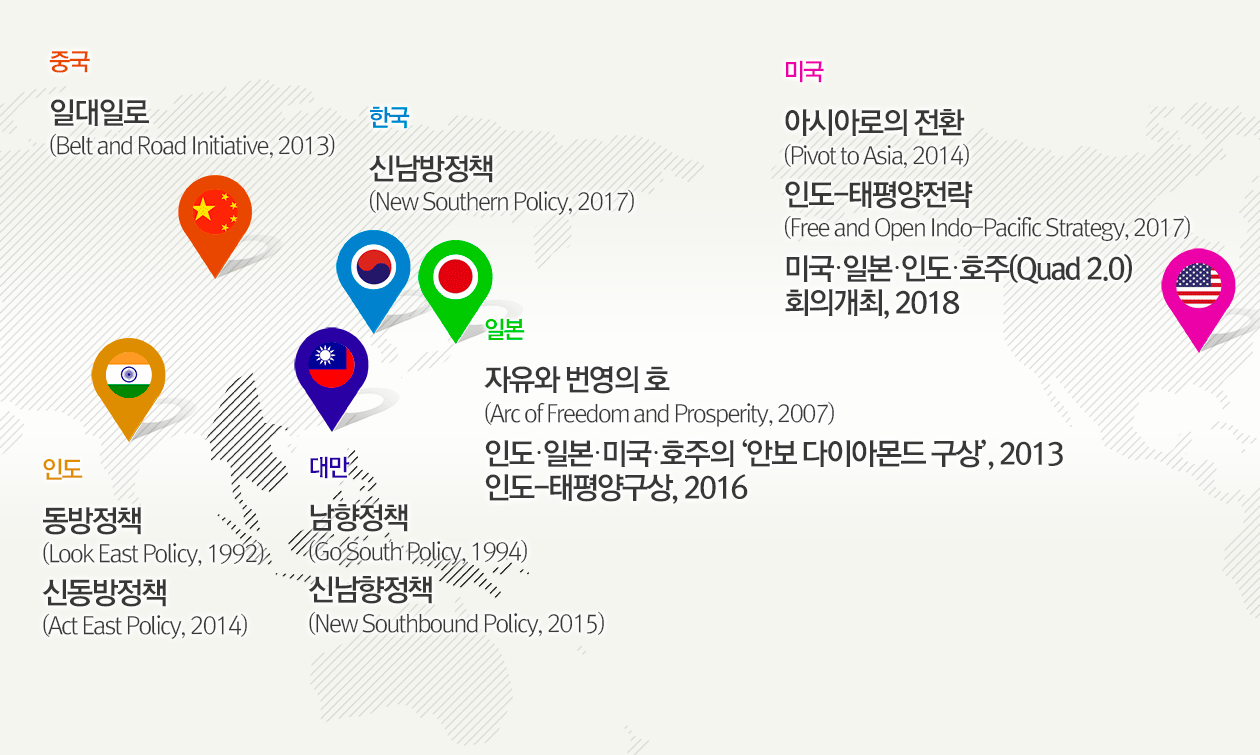

Since the establishment of the sectoral dialogue partnership in 1989, Korea has developed close ties in various fields with ASEAN. Shortly after President Moon Jae-in came into office in May 2017, he launched the New Southern Policy to further strengthen relations with ASEAN. This paper aims to analyze the characteristics of the New Southern Policy through comparisons with past policies and suggest its future directions. The rivalry among major powers such as the U.S., China, and Japan increases uncertainty in the Asia-Pacific region. In this regard, this paper also looks at how Korea, as a middle power, should respond to initiatives of major powers such as the Indo-Pacific Initiative of the U.S. and Japan and Belt and Road Initiative of China.

Kim Young-sun (Visiting Scholar at the Seoul National University Asia Center)

ASEAN-Korea Relations and the Background of the New Southern Policy

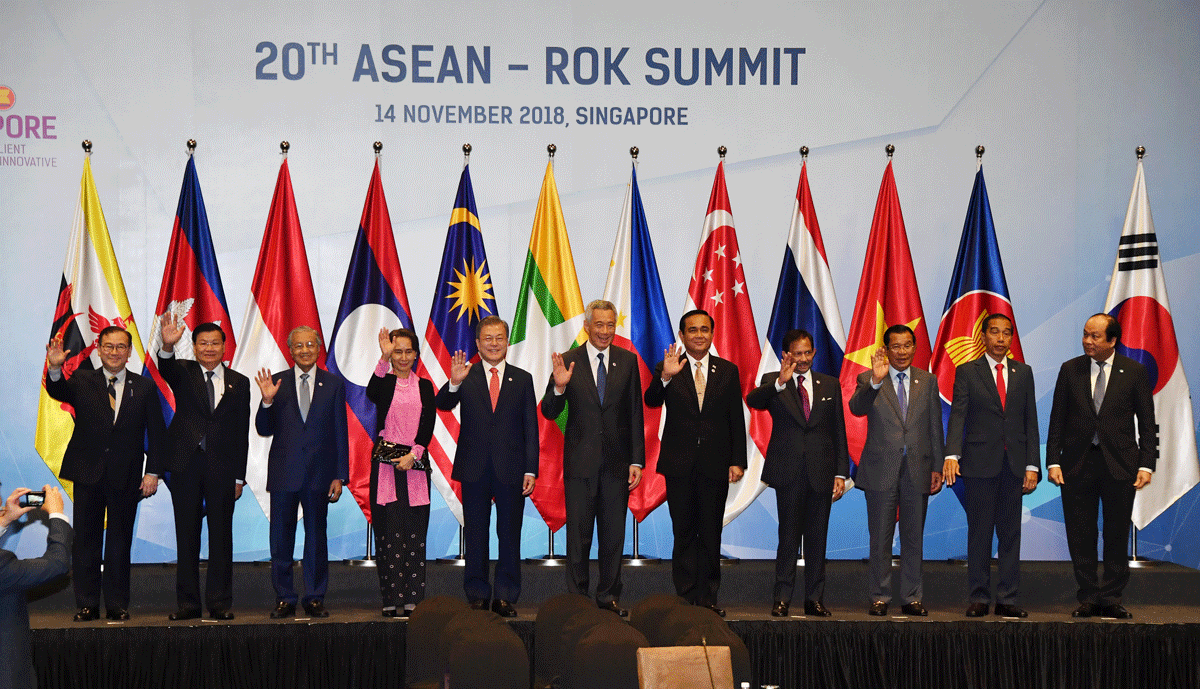

Soon after taking office in May 2017, President Moon Jae-in launched the New Southern Policy to bring relations with India and ASEAN to the same level as that of the four major powers and dispatched a special envoy to ASEAN (Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam). For the first time in history after the inauguration of a new administration, Korea dispatched a special envoy to countries other than the four major powers. This has been seen as a new start for strengthening ties with ASEAN.

Although the Korean government pursued diplomatic efforts to establish official relations with ASEAN in the late 1970s, it was not able to initiate the Sectoral Dialogue Partner relations until 1989 due to passive attitude of ASEAN. Korea was accorded a Full Dialogue Partner status by ASEAN two years later and had been making remarkable progress over the past 30 years. In 2004, ASEAN and Korea announced the Joint Declaration on Comprehensive Cooperation Partnership and elevated relations to a Strategic Partnership in 2010. Apart from the annual ASEAN-Korea Summit that takes place on the occasion of the ASEAN Summit, ASEAN-Korea Commemorative Summits were held in 2009 and 2014 in Jeju Island and Busan Metropolitan City respectively to celebrate the 20th and 25th anniversary of relations[1]. To further facilitate closer cooperation, Korea established its Mission to ASEAN in Jakarta in 2012, in the city where the ASEAN Secretariat is located. In November 2017, President Moon Jae-in unveiled the ‘ASEAN-Korea Future Community Vision’ on the occasion of his visit to ASEAN countries. As the core principles of the New Southern Policy, this initiative outlined 3Ps; a ‘people community’ where people connect heart to heart, a ‘prosperity community’ that thrives through reciprocal economic cooperation, and a ‘peace community’ that contributes to peace in Asia through security cooperation.

In fact, ASEAN and Korea have been developing close cooperative ties with one another[2]. However, we need to look into the background and real meaning of President Moon’s launching of the New Southern Policy. In the past, ASEAN officials pointed out that Korea has been treating AESAN relations as transactional rather than as an independent diplomatic agenda. In its external relations, Korea focused on the threat from North Korea and gave priorities to major powers, which hampered the development of ASEAN-Korea relations (Koh 2018; ERIA 2019). Thus, the ASEAN countries welcomed the New Southern Policy that puts much significance on the region.

Since its establishment in 1967, ASEAN brought peace and prosperity to the region for the past half century. Additionally, the ASEAN Community was launched at the end of 2015, with the motto ‘One Vision, One Identity.’ Today, ASEAN is regarded as one of the most dynamic regional cooperation organizations. The ASEAN Community is comprised of three pillars, the Political Security Community (APSC), Economic Community (AEC), and Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). The Community is expected to accelerate the ASEAN integration process and contribute to regional peace and prosperity. ASEAN, with a population of 650 million and a GDP of 2.8 trillion dollars, is situated in a location that has strategic importance across Asia, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. ASEAN’s steady growth and its great potential for future development further highlight the significance of ASEAN in the region. In return, the U.S., China and Japan, as well as India, Australia, and the EU are strengthening cooperation with ASEAN. As the Korean economy was largely dependent on China, Korea became more aware of the importance of developing relations with ASEAN after experiencing disputes over the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system. ASEAN emerged shortly after as Korea’s ‘post-China’. In that regard, the New Southern Policy Initiative was timely and meaningful as it suggested a clear vision and strategy toward ASEAN.

Together with the New Northern Policy that targets the Far East and Eurasia regions, the New Southern Policy aims to create a ‘prosperity pillar’ and promote the Northeast Asia Plus Community of Responsibility by connecting this to a ‘peace pillar.’ In addition, the New Southern Policy will help enhance strategic leverage by expanding autonomous space in the rivalry between major powers by pursuing diversification (이재현 2018).

출처: 연합뉴스

ASEAN Policies of Other Countries

‘The only certainty is uncertainty itself (Natalegawa 2018).’ This clearly depicts the current geo-strategic situations in Asia, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. Uncertainty and unpredictability are growing in this region due to the increasing Chinese influence, the emerging importance of India, the rivalry between major powers, the U.S.-China trade war, prevailing protectionism, and tendency toward national interests. In the midst of restructuring regional order, the geopolitical importance of ASEAN is growing, and ASEAN strongly insists on maintaining the ‘ASEAN Centrality.’ As a result, not only the U.S., Japan, and China, but also India and Australia are strengthening their approach to ASEAN. Then, how should Korea, as a middle power, respond to this changing regional order? Moreover, it is important to look into the implications that the ASEAN policies of other countries have on the New Southern Policy, and how the New Southern Policy can differentiate itself from them.

After Japan first established the informal dialogue relations with ASEAN in 1973, ASEAN accorded the Full Dialogue Partner Status to Japan in 1977. Since the announcement of the ‘Fukuda Doctrine’ in the same year, Japan has strengthened and broadened its relations with ASEAN in various fields ever since (Shiraishi and Kojima 2014). Japan’s ASEAN policy is an important part of its broader strategy to counterbalance the influence of an emerging China while promoting political, economic, and socio-cultural cooperation with ASEAN. Japan officialized the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy’ in 2016 based on the ‘Arc of Freedom of Prosperity’ concept revealed in 2007 and the idea of the ‘Democratic Security Diamond’ announced in 2012 that covers India, Japan, the U.S., and Australia. Although the degree of economic cooperation and people-to-people exchanges between Japan and ASEAN has slightly decreased recently, Japan is the 4th largest trading partner to ASEAN after China, the EU, and the U.S. as of 2017. Moreover, Japan is the 2nd largest investor for ASEAN after the EU. Furthermore, Japan offers the largest development cooperation assistance to ASEAN among external partners, particularly on 4th Industrial Revolution projects, human resources development, connectivity projects, cybersecurity and transnational crime issues, and youth exchange projects[3]. Along with this, Japan is contributing to fashioning ASEAN’s policy directions by assisting the process of completing the ASEAN Community Vision and the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity through supporting the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA). In addition to this, Japan also places great significance on cooperation with Mekong countries and hosted the 10th Mekong-Japan Summit in October 2018. During the Summit, the ‘Tokyo Strategy 2018’ was adopted to promote Mekong-Japan cooperation further[4].

ASEAN-China Dialogue Relations commenced in 1991, and the relationship was elevated to the strategic partnership in 2003. After signing the China-ASEAN FTA in 2010, trade and investment between the two surged. China became the biggest trading partner to ASEAN, and its investment stood as the third largest after the EU and Japan as of 2017. During the state visit of President Xi Jinping to Indonesia in 2013, he suggested cooperating on the construction of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which is the sea route part of the Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese influence in ASEAN is growing from these large-scale cooperation projects. In November 2018, China and ASEAN announced the ‘ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership Vision 2030’ for the 15th anniversary of the strategic partnership[5] and aimed to increase the two-way trade to 1 trillion dollars and two-way investment to 150 billion dollars by 2020[6]. Additionally, the 2nd Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Summit was held in Phnom Penh in January 2018 to strengthen China-Mekong cooperation. On this occasion, China promised to provide large scale assistance to Mekong countries. However, the South China Sea disputes and growing concerns over the Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure projects are challenges for China to overcome.

ⓒ DIVERSE+ASIA

India and Australia held special summits with ASEAN as well in January and March 2018 in New Delhi and Sydney respectively to strengthen cooperation with ASEAN[7]. Australia became the first of ASEAN’s dialogue partners in 1974 and has been providing practical assistance, mainly in the areas of human resource development and capacity building. Australia is contributing to developing ASEAN as a regional cooperation organization that lives up to the rules-based order and other universal values such as good governance and human rights. India began to strengthen cooperation with ASEAN through the Look East Policy in 1992, and since the Narendra Modi administration took office in 2014, India launched the Act East Policy to further facilitate active engagement with ASEAN and the region (김찬완 2018). While maintaining its traditional line of non-alignment, the Modi administration, standing for ‘strong India’, sides with the Indo-Pacific Strategy of the U.S. and Japan to limit the growing Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean. As a leading middle power, India is hoping to cooperate with ASEAN and Korea in the process of forming a new regional order (조원득 2018).

The Tsai Ing-wen administration that came into office in 2015 is also actively promoting cooperation with ASEAN through the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan, which faces diplomatic constraints due to its relations with China, launched the Go South Policy in 1994 to pursue substantive cooperation with ASEAN under the Lee Teng-hui government. The Tsai administration is focusing on expanding partner relations beyond ASEAN to South Asia and Oceania and promoting people-centered reciprocal partnerships through ‘warm power’ diplomacy (Yang and Chiang 2018; Bing 2017).

The U.S. has focused on ASEAN relations as part of its Asia-Pacific strategy. The U.S. and ASEAN established the Dialogue Relations in 1977, and the Obama administration deepened its commitment to the region through its pivot to Asia and rebalancing policy. U.S.-ASEAN relations were elevated to a Strategic Partnership in 2015 and the U.S. hosted the ASEAN-U.S. Special Leaders’ Summit in February 2016 in Sunnylands, California[8]. After President Trump came to office in January 2017 with his ‘America First’ vision, he put forth the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy’ during a visit to Asia in November as a new strategy. Then, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) meeting between the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia, was revived to deepen security cooperation. The Indo-Pacific Strategy of the U.S. aims to develop free and open maritime order in the region, bringing stability and prosperity for every country as well as securing peace. The strategy rests on three pillars: one, promoting established principles such as the rule of law and freedom of navigation, two, pursuing economic prosperity of the region by improving connectivity, and three, securing peace and stability through expansion of initiatives. The U.S. did not hide the fact that the strategy aims to counterbalance China and expressed that it would not tolerate authoritarianism and aggression in the region. The Indo-Pacific Strategy can be seen as an attempt to build and strengthen alliances to maintain existing regional order and contain China, which is seen as a challenge to the U.S.-led liberal democratic order (정구연 외 2018).

Indo-Pacific Strategy and New Southern Policy

However, there are subtle differences in the stance of the countries involved in the Indo-Pacific Strategy regarding the perception of China’s threat and countermeasures. On the occasion of Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s visit to China in October 2018, Tokyo sought to build cooperative relations with Beijing. Japan and China agreed to develop joint initiatives for infrastructure projects in third countries, resulting in Japan’s indirect involvement in the Belt and Road Initiative. India and Australia also feel burdened by putting continuous pressure on China due to the significance of economic relations (China is the biggest trading partner for both countries). The stance of ASEAN is even more complicated. ASEAN has close economic ties with China and traditionally has been maintaining a non-alignment position. ASEAN avoids being caught up in the U.S.-China rivalry and insists that ASEAN Centrality, the core of ASEAN diplomacy, should not be undermined by this.

The Korean government needs to thoroughly evaluate the Indo-Pacific Strategy and the Belt and Road Initiative and seek ways to cooperate with both the U.S. and China. In the process of restructuring regional order, it is important for Korea to figure out the positioning of the New Southern Policy. Since the Indo-Pacific Strategy has values and specific projects that are shared by Korea, it is necessary to give positive consideration to and update cooperation schemes with the U.S. However, Korea, as well as the other countries, would like to avoid the situation where they are forced to make a choice due to the deepening rivalry between the U.S. and China. Prime Minister of Singapore, Mr. Lee Hsien Loong, highlighted that ‘it is very desirable’ for ASEAN ‘not to have to take sides’ in his speech at the ASEAN Summit. Therefore, Korea should expand its strategic space of diplomacy by cooperating with like-minded countries such as ASEAN member states, India, and Australia, and strive to find ways for a new regional order to develop in an inclusive manner that does not target any specific country (조양현 2017, 최원기 2018).

Success Strategies of the New Southern Policy

What should be done to make the New Southern Policy successful?[9] ASEAN countries welcomed and favorably assessed the New Southern Policy. However, they expect a concrete roadmap of implementation and core projects to be presented. Korea should not repeat the failures of the previous governments where ASEAN relations were neglected when Korean peninsular problems or issues with major powers emerged.

First, we must maintain the momentum while refining the vision, strategy, and implementation roadmap of the New Southern Policy. As the policy is somewhat incomplete in incorporating universal values such as democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, there is a need to bring out these elements considering that ASEAN also places great emphasis on ‘Rules-based ASEAN.’ As for Korea supporting ASEAN integration and development, it can highlight the importance of ASEAN strengthening the ‘Rules-based Multilateral System’ through the promotion of effective multilateralism (ASEAN 2019).

The Plan of Action to Implement the Joint Declaration on Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity 2016-2020 covers a wide range of cooperation in various fields; however, it fails to stipulate specific projects. For cooperation projects, it is necessary to narrow down the focus and concentrate on specific goals. Therefore, immediate development of impactful flagship projects in each sector is needed, and thorough implementation should follow.

Second, we must establish short, mid, and long-term goals for ASEAN-Korea relations and ultimately define what type of relations to pursue. The 3Ps of the New Southern Policy contain visions of creating a ‘peace community that is mutually prosperous and people-centered.’ However, this needs further clarification. To create a people-centered future community, Korea and ASEAN should be able to recognize each other as a common destiny, a true friend that shares hearts and minds. It is important not to be so caught up with making short-term benefits or rushing to merely produce tangible outcomes. Qualitative development based on trust should be the core principle, going beyond quantitative elements such as the amount of trade and investment and the number of people-to-people exchanges.

Third, it has been announced that Korea will upgrade its ties with ASEAN to the same level as that of the four major powers. Here, we need to have clear understandings on what it truly means to upgrade economic, political, and strategic relations with ASEAN to the level we have with the major powers. If this is not accompanied by specific actions and simply remains diplomatic rhetoric, it might cause disappointment in relations. For example, we need to clarify what kind of role and contribution ASEAN is expected to make regarding North Korea and Korean peninsula issues and also to what extent we intend to develop the strategic partnership with ASEAN.

Fourth, we should avoid approaching ASEAN relations solely based on the Korean perspective. Korea must consider the changes in the political, economic, and socio-cultural environment on both sides and reflect the interests and priorities of the partner. For this, more active communication with one another is important. The New Southern Policy should focus on creating a mutually beneficial partnership that leads to sustainable cooperation. That way, Korea can eventually maximize the benefits it receives from ASEAN relations. ASEAN is a dynamic partner with a high growth potential that is being perceived as a ‘post-China’ destination. The ASEAN Community was launched in pursuit of integration in political security, economic, and socio-cultural fields. To achieve this, enhancing connectivity and narrowing the development gap are the important tasks for ASEAN. Thus, Korea should place more emphasis on cooperation projects that improve ASEAN connectivity and support technology development to assist the integration process further while also contributing to the reduction of development gaps. What ASEAN expects the most from Korea, the country that achieved remarkable development after struggling through colonial rule, war, and poverty, is the sharing of its development experience and know-how.

Fifth, we must be able to present differentiated policies and projects while at the same time seeking collaboration with the ASEAN policies pursued by other countries. We need to demonstrate how our policy is different and what has been changed from the policies of the previous governments. It is challenging for Korea to compete with major powers like China and Japan in terms of the scale of cooperation. ASEAN countries are also concerned about the growing influence of the major powers in the region as their assistance grows. We need to seize this opportunity and use it to our advantage as a middle power. Unlike major powers, Korea has neither historical/territorial disputes nor hegemonic interests in the ASEAN region. Thus, as middle powers, ASEAN and Korea can develop a true and lasting partnership. It is also crucial for ASEAN-Korea relations to go beyond a bilateral partnership and play the role as middle powers contributing to the facilitation of peace and prosperity in the region.

출처: 연합뉴스

Sixth, policies toward ASEAN and individual ASEAN member countries should be complementary and harmonious. We need to make an effort to understand what tasks are required to improve the integration process of ASEAN and facilitate minilateral cooperation in the Mekong region as well as cooperation with each ASEAN country. Also, we should have a diversified strategy toward each ASEAN country, as leaning too much on particular countries such as Vietnam can be a risk factor, and it may burden the ASEAN integration process.

Seventh, it is imperative that the control tower plays a role in coordinating projects scattered in different departments of central government, local governments and related organizations to effectively implement policies and projects. We need to set up the system responsible for implementing the New Southern Policy and ensure we have professionals, experts, and the necessary budget.

Eighth, the New Southern Policy will not be successful unless it has the consistency, support and understanding of the people, and close cooperation with ASEAN. Korea also faces many challenges under the uncertainty of the global economy. We need to find new growth engines and markets. In this respect, ASEAN is one of our optimal strategic partners. We should avoid having a short-sighted attitude about why we should help to strengthen the industrial capacity of ASEAN and increase Official Development Assistance (ODA) even though we have our own urgent issues to address. We cannot expect the success of the New Southern Policy without public understanding and support for a reciprocal partnership with ASEAN. Moreover, it is important that ASEAN and Korea have unbiased perceptions of one another through mutual understanding. Based on all these, the development of a genuine partnership between ASEAN and Korea can be achieved.

Last but not least, ASEAN needs to be encouraged to play a more active role in contributing to the denuclearization of North Korea and assist the process of opening up its economy to support North Korea becoming a responsible member of the international community. Through this, ASEAN and Korea would be able to strengthen the cooperation mechanism that brings peace and stability to the region. It is also meaningful that the two historic U.S.-North Korea Summits were held in ASEAN countries, namely Singapore and Vietnam respectively. All 10 ASEAN countries have diplomatic relations with North Korea, and a number of them have resident embassies there. North Korea highly values its ties with ASEAN countries as well. In 1995, the Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone Treaty (SEANWFZ) was signed, and ASEAN acknowledged the North Korean nuclear issue as a major source of danger in the region. This clearly shows ASEAN’s support for the position of Korea and the international community, namely the complete denuclearization of North Korea. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Vietnam and Singapore are being mentioned as models for North Korea’s reform.

We could more effectively bring about reforms in North Korea by using close cooperative ties with ASEAN. North Korea joined the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in 2000 and has been regularly attending the event every year. Moreover, North Korea acceded to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC) in 2008. In this regard, we should actively seek ways to engage North Korea in the cooperative mechanisms of ASEAN. On the other hand, some concerns have been expressed over the possible decrease in the entry of Korean companies into the ASEAN market due to the facilitation of inter-Korean economic cooperation. However, this should not be viewed from the zero-sum perspective. Ultimately, inter-Korean reconciliation and cooperation will serve as a catalyst to bring greater benefits as a whole rather than harming the ASEAN-Korea partnership. It is necessary to develop this momentum into a new cooperation opportunity between the two Koreas and ASEAN.

Specific Cooperation Projects

To increase momentum in the development of ASEAN-Korea relations through the New Southern Policy, it is necessary to pursue concrete cooperation projects. The following projects can be reviewed according to the 3P visions in the New Southern Policy.

<Table> Examples of the cooperation projects of the New Southern Policy

| 3P Categories | Sub-categories | Detailed Strategies |

| People | Raise Awareness | · Projects to raise awareness and promote mutual understanding: providing support to ASEAN studies in Korea and Korean studies in ASEAN · Establishment of the ASEAN Studies Centre in Korean universities and research institutes, and strengthening networks and cooperation with ASEAN Studies Centre in ASEAN · Project to build a network of ASEAN-Korea think tanks and facilitate exchange · Establishment of the regular ASEAN-Korea Forum at the international level[10] · Designation of the ASEAN-Korea Day |

| Cultural Exchange | · Organizing joint cultural projects by the ASEAN Culture House in Busan and the ASEAN Cultural Center in Bangkok※ This year has been designated as the ASEAN Year of Culture | |

| Capacity Building | · People-to-people exchanges, human resource development, and capacity building projects · Strengthening youth exchange projects to cultivate future leaders (expanding scholarship and training programs) |

|

| People-to-people exchanges and Migration | · Simplified visa process for ASEAN nationals visiting Korea · Improvement in the Employment Permit System and protection of basic rights of multi-cultural families and migrant workers |

|

| Prosperity | Enterprise Support | · Establishment of a capacity building centre and R&D centre for the 4th industrial revolution technologies[11] · Projects to support small and medium-sized enterprises (further developing the TASK, TVET projects) · Projects to promote economic and industrial policy research institutes (V-KIST in Vietnam and MDI in Myanmar) |

| Connectivity | · Expanding the ‘ASEAN Connectivity Forum’ organized by the ASEAN-Korea Centre (in cooperation with ADB, World Bank, AIIB, ESCAP, etc.) | |

| FTA | · Accelerating FTA negotiations (RCEP, upgrading AKFTA, and bilateral CEPA with Indonesia, Malaysia, etc.) | |

| Peace | Future Vision | · Establishment of the ASEAN-Korea Eminent Persons Group to suggest future visions and directions[12] |

| Mutual Understanding | · Establishment of peace parks or memorial centres in Indochina countries that could line with the DMZ Peace Park in Korea to symbolize the peace and prosperity of ASEAN and Korea · For this project, it is necessary to remove mines and explosives and rehabilitate the community[13] |

|

| Regional Security | · Strengthening cooperation on non-traditional security and transnational issues |

Source: author and the suggestions made by the Southeast Asia Research Team at the Seoul National University Asia Center in its 「Strategies of Elevating the Mekong-ROK Summit」

ASEAN, Korea’s Key Partner

ASEAN and Korea have already developed into key partners for each other. It was timely and relevant to launch the New Southern Policy in that it considered enhanced ASEAN-Korea relations as one of our main diplomatic agendas. In this respect, the realization of the New Southern Policy is a very important task for the Moon Jae-in administration. In addition, the policy should not be a temporary initiative of one specific administration but rather it must be pursued with consistency and continuity. In that process, the development of the relationship between ASEAN and Korea should be driven primarily by a ‘people-centered’ philosophy. The genuine and sustainable partnership can be achieved only when the two perceive each other as a common destiny that shares hearts and minds based on mutual understanding and respect.

This year offers an excellent opportunity to make significant developments in the New Southern Policy. The 2019 ASEAN-ROK Commemorative Summit will be held in Busan late this year to celebrate the 30th anniversary of ASEAN-Korea relations, and the 1st Mekong-ROK Summit will also be held on this occasion. The Commemorative Summit is held for the third time following 2009 and 2014, and Korea will be the first country to have three commemorative summits with ASEAN among the 10 Dialogue Partners. The Korean government needs to elaborate and suggest the vision, strategy, and specific implementation roadmap of the New Southern Policy that reflect long-term goals rather than instant results. In order to make the New Southern Policy a success, the Korean government’s unwavering stance, steady execution, people’s support and understanding, and close cooperation with ASEAN are a must. The ASEAN-ROK Commemorative Summit and the Mekong-ROK Summit to be held this year should be a meaningful turning point for ASEAN-Korea relations.

About the author:

H.E. Ambassador Kim Young-sun

graduated from Seoul National University with a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science and received a Master’s degree at Keio University, Japan. He served as the Ambassador of the Republic of Korea to the Republic of Indonesia and as the Secretary General of the ASEAN-Korea Centre. He is a visiting scholar at the Seoul National University Asia Center, and his research fields are ASEAN-Korea relations and the politics of Southeast Asia. He also publishes columns regulary in a Korean daily newspaper, entitled ‘Kim Young-sun’s Closer Look into ASEAN (김영선의 ASEAN 톺아보기).’

[1] Joint declarations were issued during the summits in 2009 and 2014. Title of the joint declaration issued at the 2014 ASEAN-ROK Commemorative Summit is ‘Our Future Vision of ASEAN-ROK Strategic Partnership, ‘Building Trust, Bringing Happiness.’

[2] ASEAN is the 2nd largest partner of Korea in the areas of trade, investment and overseas construction as of 2017. Also, ASEAN is the top travel destination for Koreans. Meanwhile, Korea is the 5th largest trading and investment partner for ASEAN among 10 dialogue partners, and the number of Koreans visiting ASEAN is the 2nd highest after China among all non-ASEAN countries.

[3] During the ASEAN-Japan Commemorative Summit celebrating the 40th anniversary of ASEAN-Japan relations, the ‘Vision Statement on ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation: Shared Vision, Shared Identity, Shared Future’ (November 14, 2018) was issued.

[4] ‘Tokyo Strategy 2018 for Mekong-Japan Cooperation’ (October 9, 2018) proposes three main pillars of cooperation; Vibrant and Effective Connectivity, People-Centered Society, and Realization of a Green Mekong.

[5] ASEAN-China relations is well described in the ‘ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership Vision 2030’ (November 14, 2018)

[6] This is included in the Chairman’s Statement of the 21st ASEAN-China Summit to Commemorate the 15th Anniversary of ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership (November 14, 2018)

[7] This is presented in the Delhi Declaration of the ASEAN-India Commemorative Summit to Mark the 25th Anniversary of ASEAN-India Dialogue Relations (January 25, 2018) and the Joint Statement of the ASEAN-Australia Special Summit: the Sydney Declaration (March 18, 2018).

[8] The U.S. policy toward ASEAN is elaborated in the ‘Joint Statement of the ASEAN-U.S. Special Leaders’ Summit: Sunnylands Declaration (February 17, 2016)

[9] The author addressed this question in a column contributed to 『Chindia Plus』 Vol. 127 in 2017, entitled ‘신남방정책- ‘포스트차이나’ 아세안을 잡아라’

[10] ASEAN-Korea conferences and forums are being held sporadically at a number of different organizations; however, it is necessary to launch a representative international forum. In the case of Taiwan, it annually organizes the Yushan(玉山) Forum.

[11] In the case of Japan, it focused on cybersecurity as one of the major agenda and opened the ASEAN-Japan Cybersecurity Capacity-Building Centre in Bangkok.

[12] ASEAN-ROK Eminent Persons Group was established in 2009; however, it needs new approaches and understandings due to a rapidly changing geostrategic environment.

[13] This can be one of the projects of the Mekong-ROK Summit. In fact, ASEAN and Korea agreed to cooperate with the ASEAN Regional Mine Action Centre (ARMAC) on mines and explosives related matters during the 2014 ASEAN-ROK Commemorative Summit.

Reference

- 김찬완. 2018. “모디정부 외교정책의 결정요인: 지속과 변화를 중심으로,” 『남아시아연구』 Vol. 24, No.2.

- 이재현. 2018. “신남방정책이 아세안에서 성공하려면?” 『이슈브리프』 No.24(아산정책연구원).

- 정구연,이재현,백우열,이기태. 2018. “인도태평양 규칙기반 질서 형성과 쿼드협력의 전망,” 『국제관계연구』 Vol.23, Vol.2.

- 조양현. 2017. “인도·태평양전략(Indo-Pacific Strategy)구상과 일본외교,” 『IFANS 주요국제문제분석』 Vol.63.

- 조원득. 2018. “한-인도 정상회담 평가와 신남방정책에 대한 함의,” 『IFANS 주요 국제문제분석』 Vol. 26.

- 최원기. 2018. “‘인도-태평양 전략’의 최근 동향과 ‘신남방정책’에 대한 시사점,” 『IFANS FOCUS』.

- 최경희·김태윤·백용훈·엄은희·이준표. 2018. “신남방정책·한-아세안관계 30주년, 한-메콩 정상회의 격상의 함의 및 전략: 3P속의 7대 우선분야,” 『2018년 외교부 정책용역과제』. 서울: 서울대 아시아연구소 동남아센터 연구팀.

- ASEAN. 2019. Joint Statement of the 22nd EU-ASEAN Ministerial Meeting(2019/01/21).

- Bing, Ngeow Chow. 2017. “Taiwan’s Go South Policy: Dejavu All Over Again?” Contemporary Southeast Asia Vol.39. No.1.

- ERIA. 2019. ASEAN Vision 2040: Stepping Boldly Forward Transforming the ASEAN Community. ERIA: Integrative Report.

- Kim, Young-sun. 2017. “ASEAN and Korea share common destiny,” Korea Herald. (2017/10/30).

- Koh, Tommy. 2018. “Three ways to improve Asean-South Korea ties.” The Straits Times (2018/07/03).

- Natalegawa, Marty, 2018. Does ASEAN Matter? Singapore: ISEAS.

- Shiraishi, Takashi and Kojima, Takaaki. 2014, “An Overview of Japan-ASEAN Relations.” in Shiraishi, Takashi and Kojima, Takaaki, eds. ASEAN-Japan Relations. Singapore: ISEAS.

- Yang, Alan Hao and Chiang, Jeremy. 2018.10.23. “Taiwan is Retaking the Initiative with its New Southbound Policy.” the Diplomat (2018/10/23).

*본 기고문은 전문가 개인의 의견으로, 서울대 아시아연구소와 의견이 다를 수 있음을 밝힙니다.